This is the first in a series of posts I want to write about the technical aspect of writing a voxel engine / editor. I wrote a free and open source voxel editor available on github, and I wanted to share the things I learned in the process.

Today’s post is just an introduction, where I am going to talk about the evolution of computer graphics and the advent of voxels.

The evolution of 2d graphics, from vectorial to bitmap

At the dawn of computer graphics, it was generally costly to store images as an array of pixels, since the available memory was too little. Instead vectorial art was used for large images.

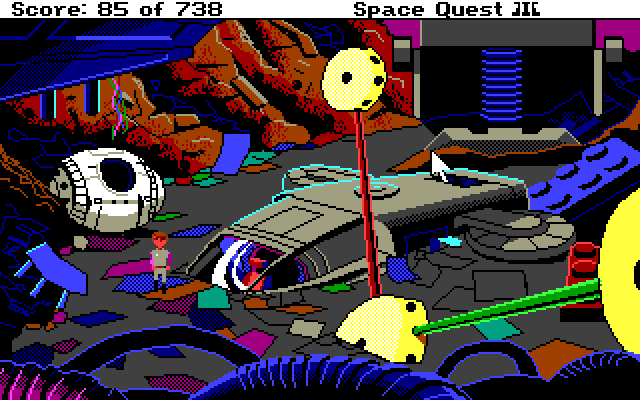

Screenshot from the game Space Quest III, released in 1989 (in my opinion the best in the series):

In this game, the backgrounds were not saved in conventional bitmap images, but as vectorial data. This youtube video (by jack) shows how the construction looks like:

A vectorial image can potentially be much smaller, since you only save data about the individual shapes.

As computer CPU and memory improved, it became possible to store images directly as 2d arrays of pixels.

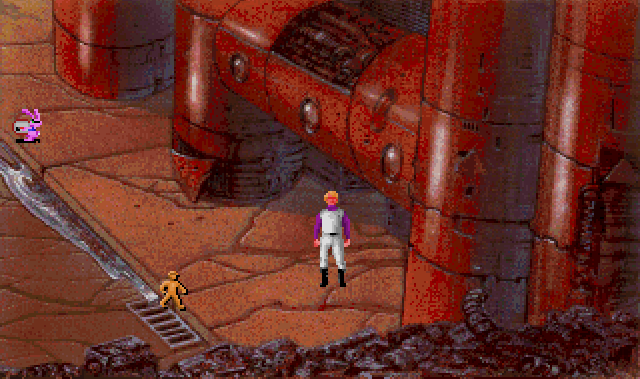

Screenshot of Space Quest IV, released in 1991, that was this time using bitmap graphics:

These days both ways of storing images, vectorial and bitmap coexists and got standardized in different file formats. For example png and jpeg store images as bitmap, while svg used vectors.

An important distinction between bitmap and vector images is that as you zoom in a bitmap image, you start to see the individual pixels, while a vectorial image always looks nice at any resolution.

![]()

3d graphics and voxels

For 3d graphics, until recently the only mainstream format was vectorial. A 3d scene is composed of individual shapes represented by vertex coordinates.

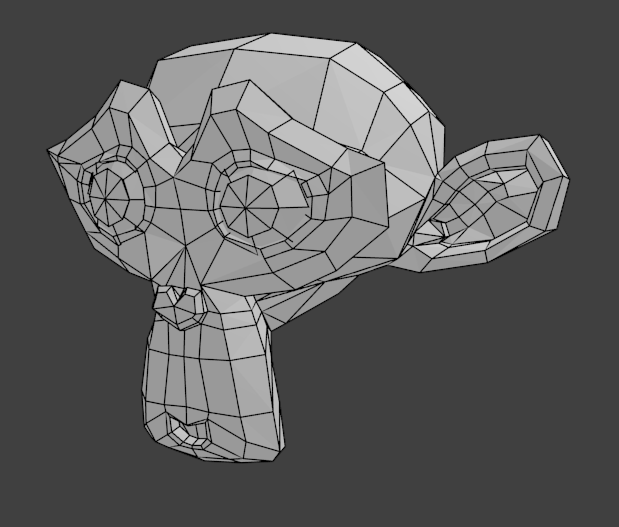

Picture of the [blender]monkey shape (suzanne) where we can see the individual polygon shapes:

As with 2d vectorial images, this is a problem if we try to apply a boolean operation on a volume, because it can quickly increases the complexity of the model:

We can see that the number of vertices increases in the operation. Also the algorithms doing the tessellations are usually not fast. For this reason not many real time video games allow for destructive manipulation of the environment in a realistic way.

Just like with 2d images, we can also store 3d images as a matrix of pixels, though in that case we call them voxels (volumetric pixel).

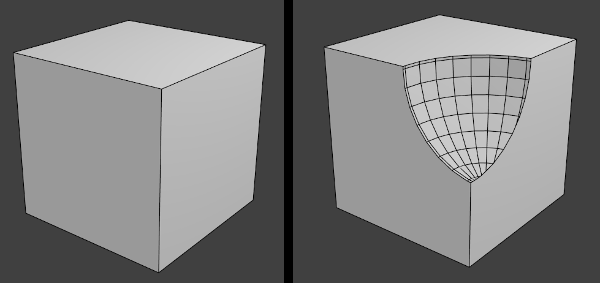

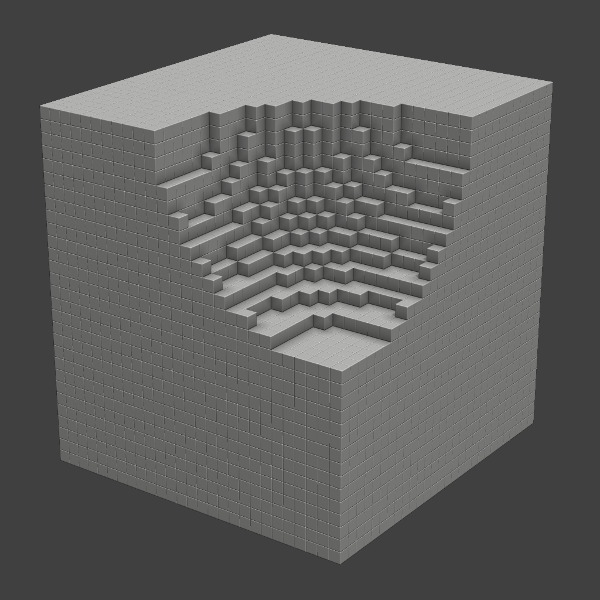

Here is what a carved 3d cube looks like when rendered as voxels:

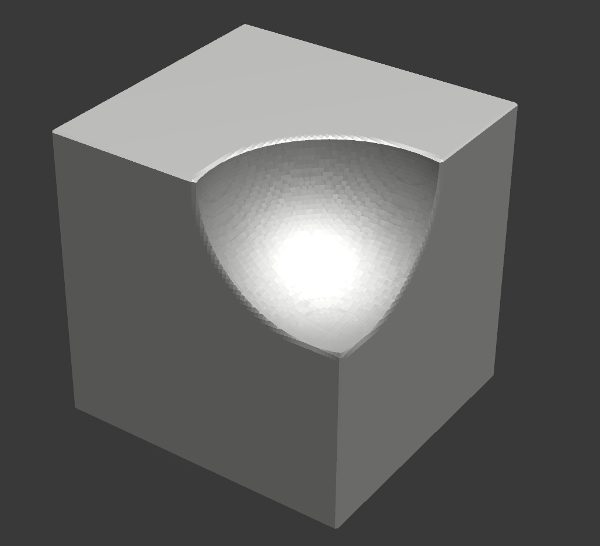

It looks voxelated, because the resolution is not high enough, if we increase the number of voxels, and use a smoothing rendering algo (I’ll talk about it in a future post) we can get something that looks more realistic:

The interesting part about it, is that any kind of boolean operation on a voxel model is possible without any restriction, and at a fixed cost.

Just like with 2d, I think we might start to see more voxel content, because computer performances reaches a point where it becomes feasible, even in real time rendering.

My guess is that AAA games are probably not going to use voxel rendering as primary engines any time soon though, since vectorial 3d models are still far from reaching the complexity at which it would become simpler to use voxels.

That being said, outside of the realistic looking games market, we see the emergence of voxel games. The most famous examples being of course minecraft (and voxel invaders ;) )

In the next posts, I will detail the technical challenges faced when doing voxel graphics and go into the details of goxel code.